Icicles hang from a San Antonio city limit sign along the access road of I-10 and Ralph Fair Road. Drive through San Antonio and you’re likely to see at least one sign saying “leaving San Antonio” or “entering San Antonio."

Kin Man Hui/Staff photographer

San Antonio Express-News

Timothy Fanning, San Antonio Express-News

Drive through San Antonio and you’re likely to see at least one sign saying “leaving San Antonio” or “entering San Antonio.” Sometimes those signs are only a mile or two apart.

Olmos Park is only about 1 square mile.

The reason? The Alamo City completely or partly surrounds nearly a dozen cities. Another dozen are contiguous to or a short distance from San Antonio’s outer limits.

Alamo Asks is a new series in which we invite you to submit questions about San Antonio for us to research.

Deborah Broome wanted to know: “Why does San Antonio have so many little separate cities inside its perimeter? And are those cities, like Leon Valley, in any published population totals?”

These cities formed — in waves — for the same basic reason: fear of being annexed by San Antonio in its aggressive effort to push its boundaries outward, said Char Miller, former Trinity University history professor and author of “West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement.”

The first wave followed the post-World War I surge in growth north, northeast and northwest of San Antonio. The magnet that drew out the second wave of expansion, after World War II, was the building of Loop 410 and suburban malls.

The Olmos Park City Hall on Oct. 28, 2021.

Timothy Fanning

Some of these cities, such as Alamo Heights and Olmos Park, incorporated for political reasons, too, and because residents wanted to bar people of color and people with certain incomes from living there, said Miller, who is now a professor of environmental analysis and history at Pomona College in Southern California.

“They saw themselves as white enclaves and rich enclaves,” Miller said.

Some of these cities, including Alamo Heights and Leon Valley, have their own Census Bureau figures. The latest, reflecting 2022, show Leon Valley has 11,429 people.

Other of these cities have their own police, firefighters and school districts, like the Alamo Heights Independent School District. Most enjoy a strong individual identity.

“There is this enclave and feeling that we’re separate, and we feel special because of that separateness,” Miller said.

It isn’t so beneficial for the city of San Antonio.

Consider when posh Olmos Park started to develop in the mid-1920s, after the Olmos Dam went up.

San Antonio’s politicians offered various city services, including water, as long as people there stayed out of city politics.

“And that sort of worked out OK for those who were running the city in the '30s and '40s,” Miller said. “By the 1950s, they were like, ‘We really should have gotten them back in the day because imagine those houses and the property tax you could get from them,'" Miller said.

Rich, white enclaves

Alamo Heights, Olmos Park and Terrell Hills — the area’s earliest suburbs to become cities — all developed north of San Antonio’s city limits and incorporated in the 1920s and 1930s.

Over 100 years ago, the Alamo City essentially ended at Hildebrand Avenue, which was part of the 6-mile square the Spanish had designated. But those boundaries pushed outward thanks to San Antonio’s growth and the advent of the streetcar.

The area that would become the city of Alamo Heights grew thanks to a streetcar that ran northbound on Broadway.

Part of the area’s appeal to wealthy white locals was its large lots with covenants that barred their sale to anyone who wasn’t white or didn't have the capital to move in, Miller said. Alamo Heights incorporated in 1922 in an effort to create a tax haven and avoid annexation by San Antonio.

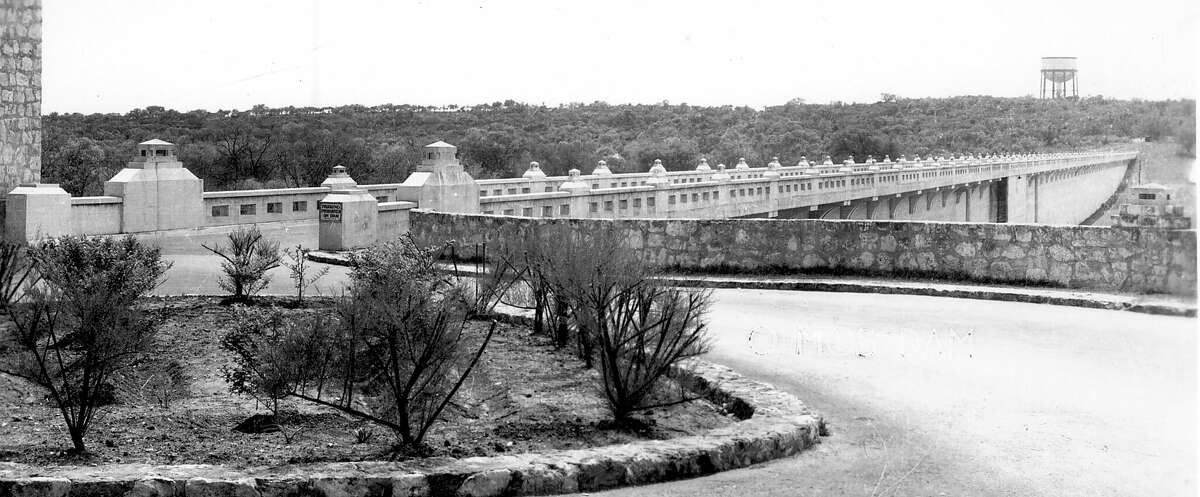

The construction of the Olmos Dam, which went up after the deadly 1921 flood, made it possible for Olmos Park and Terrell Hills to come into being — as did the automobile.

An undated photo of the old Olmos Dam roadway looking east. The roadway opened in 1926 as part of the original dam's construction. It was torn down and moved downstream from the dam in the late 1970s.

San Antonio River Authority

Some of what drew people to Olmos Park and Terrell Hills in the 1920s was the desire to get out of low-lying neighborhoods and onto the dry high ground, Miller said.

This era helped spur growth in Tobin Hill and Monte Vista — all properties of which were sold to white, middle- to upper-class people who took “extraordinary advantage” of the high ground, Miller said.

When Terrell Hills and Olmos Park incorporated in 1939, San Antonio leaders saw the writing on the wall, Miller said.

San Antonio annexed the area all around the three smaller cities, making them landlocked.

And it took other steps against them, including proposing a city dump near the suburban cities and taking Olmos Park and Terrell Hills to court in an effort to annex them. The city of San Antonio eventually dropped the case.

‘How fast can we incorporate?’

As development in San Antonio pushed northward toward what would become Loop 410, so did San Antonio’s annexation efforts. This was aided by a state law passed in the 1940s that granted cities unchecked power to annex.

“So the dynamic was: You build the roads, and the subdivisions are beginning to fill in immediately,” Miller said. “And then it becomes this sort of fight like: How fast can we incorporate before San Antonio takes us over?”

After Balcones Heights incorporated in 1948, nine other cities — more than a third of San Antonio's 25 suburbs — incorporated during the 1950s.

Seven more incorporated in the 1960s, two in the 1970s, two in the 1980s, and one in the present decade.

Leon Valley incorporated in 1952 after a newspaper reporter noticed a San Antonio City Council item about annexing the area and mentioned it to Leon Valley residents. They mobilized and became a city.

Beginning in the 1960s into the '70s and '80s, San Antonio’s goal was to capture everything there — subdivisions, hotels, shopping malls — and the valuable, accompanying tax dollars, Miller said.

The south entrance into Old Town Helotes on Old Bandera Road on Saturday, Feb. 1, 2014.

MARVIN PFEIFFER/Marvin Pfeiffer / EN Communities

“They wanted cash registers. They wanted tax dollars. They wanted property tax dollars,” Miller said. “Some of the incorporation effort is driven by competing concerns where individuals don’t want to pay city taxes.”

After the wave of incorporation during the 1950s, San Antonio came up with a plan to prevent other areas from doing the same thing.

In September 1959, a series of ordinances called for annexing 330 square miles, according to an article by political scientist Arnold Fleischmann in the book "The Rise of the Sunbelt Cities."

In a chapter in the book about San Antonio's postwar annexation, Fleischmann wrote: "The council had no intention of annexing this territory but planned to prevent suburban incorporation by having the first reading and then indefinitely delaying final passage of the proposal.

"If this annexation ordinance had been enacted, San Antonio's population would have increased by 76,000 and the city's area would have grown to nearly 500 square miles, making it the largest city in terms of area in the United States," Fleischmann wrote.

But the city abandoned the ambitious annexation plan, and nothing else City Council did seemed to stop the drive toward suburban incorporation.

In more recent times, Fair Oaks Ranch incorporated in 1980, and Helotes followed a year later. Both did so aiming to preserve their rural character and to prevent San Antonio from swallowing them up.

By incorporating, the city of Helotes was able to do what so many other cities have done: elect its own mayor and council members.

From the point of view of someone living in a city like Leon Valley, that can be a great benefit, Miller said.

“And so you feel as if you are better represented in ways that it’s a lot harder (to be) in a city of close to 2 million people that’s sprawled all over the place,” Miller said.